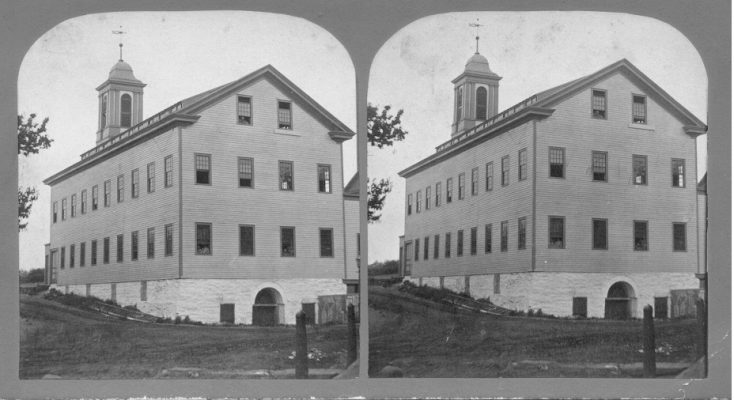

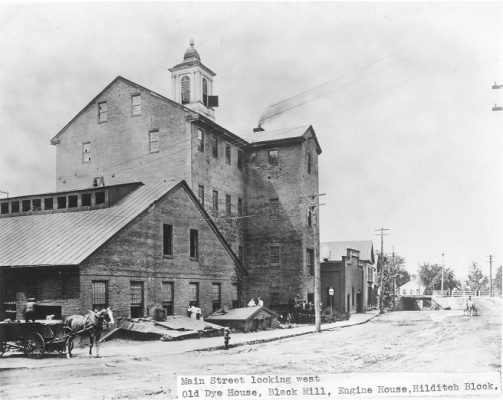

Enfield’s carpet industry was founded by Orrin Thompson, after whom Thompsonville is named. Thompson obtained a charter from the State of Connecticut and, with $35,500 in capital investments from New York carpet importers and Scottish carpet weavers he built a 14 foot high, 118 foot long dam on Freshwater brook in 1828, then proceeded to construct the first of Enfield’s carpet mills – the “White Mill” – astride the brook. The mill was completed in early 1829 and, manned by skilled weavers brought over from Scotland, was in operation by summer of that year.

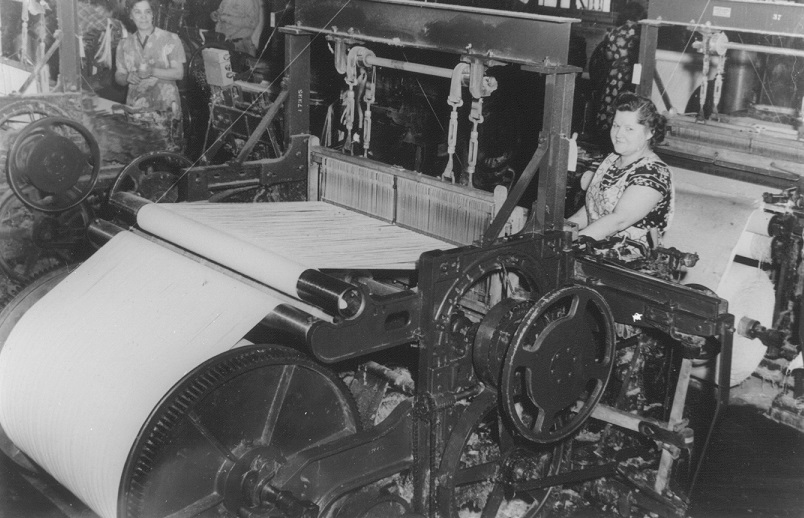

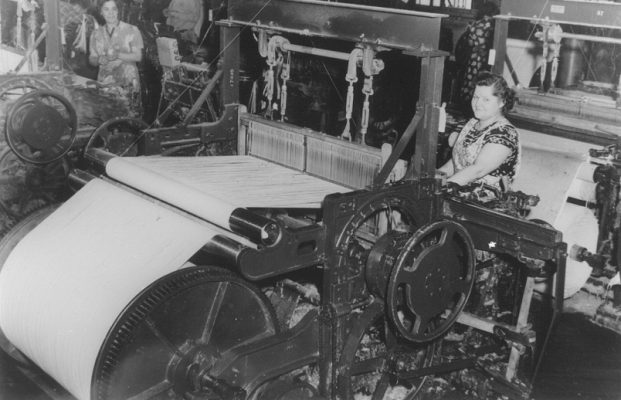

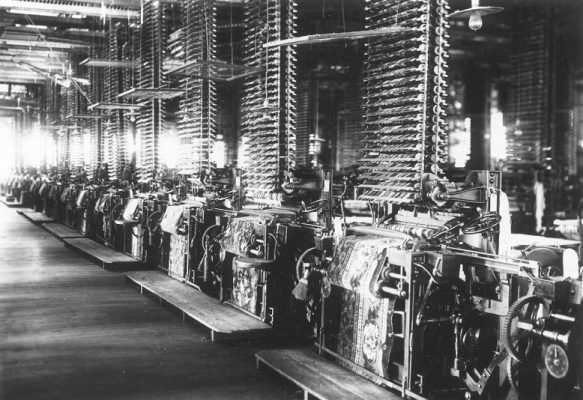

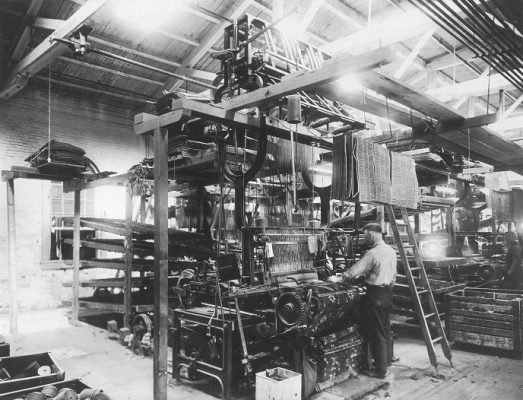

Early production consisted mostly of inexpensive flat-woven ingrain carpeting. As the mill became established other more expensive weaves, including three-ply ingrain, rugs, and loop brussels were added. By 1846 there were 230 looms in operation at the mill. Expanding production required the purchase or construction of additional mills, both in and outside of Enfield. In 1848 a new 330 foot by 60 foot brick mill was built. Over the next three years $350,000 was invested in new machinery, including nearly 150 power looms, which cut production costs by about 10%. By 1850 carpet output from the Thompsonville mills had reached 250,000 yards per year!

Unfortunately, the economic picture had changed by this time, which resulted in significant losses and bad debts that forced Thompson and Company (Orrin, Orrin’s son Henry G. Thompson, and Joseph Dean) to go bankrupt. A group of businessmen from Hartford, headed by Timothy Allyn, Edmund G. Howe, and William R. Cone, raised half a million dollars in new money and got the mill back in operation just in time for the 1854 business recession. Despite this poor timing, the newly formed Hartford Carpet Company prospered. By 1871 the mill was producing over 7000 yards of carpet per day.

New carpet lines were added by the mills, including Wilton and Moquette (a modified axminster) carpets. Other improvements to the mill included electricity and a reduction of the work week to 56 hours for the workforce of 1,800.

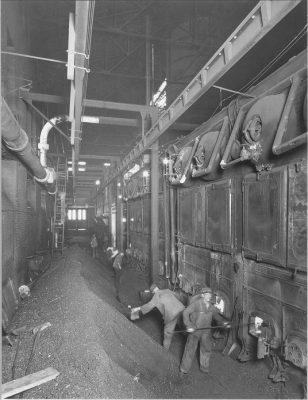

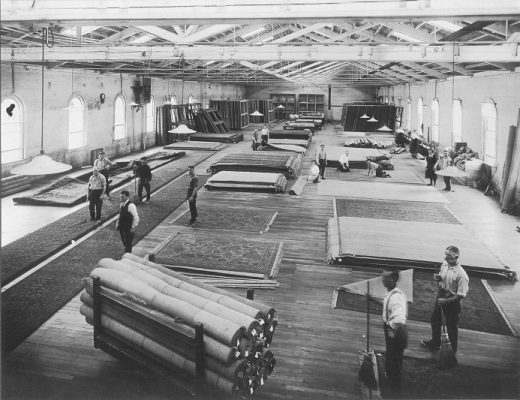

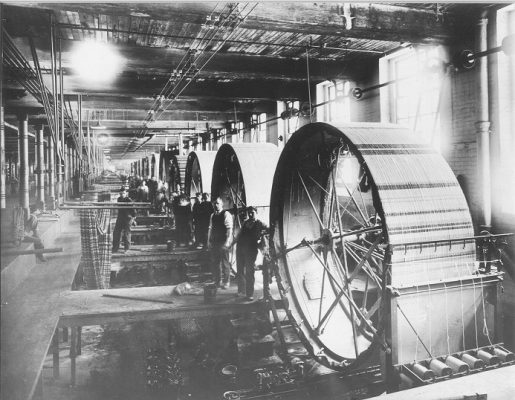

In 1901 the Hartford Carpet Company merged with the E.S Higgens & Company of New York, forming the Hartford Carpet Corporation. The merger brought with it a huge expansion and modernization program. 400,000 square feet of buildings were added in 1901 alone, including a 900 foot long tapestry mill, a worsted mill, finishing, fulling, and scouring mills, a color house, and a rug finishing department. In 1902 an axminster mill was added, as were new broad looms and a 4,000 horsepower electric plant. By 1910 there were 2,900 employees turning out 7.5 million yards of carpet per year.

In 1914 the Hartford Carpet Corporation merged with the Bigelow Carpet Company of Clinton, Massachusetts to form the Bigelow-Hartford Carpet Company. This new company was the third largest corporation in New England with a total output of over 13,000,000 yards of carpet per year at its three locations.

The years leading up to 1929 saw more innovations and improvements as the company fought competition from linoleum and other hard-surface coverings. Profits remained good and another merger took place, this time with the Sanford Carpet Company of Amsterdam, New York. It was just one month after the Stock Market crash of 1929. The newly formed Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Company, Inc. was hit hard by the depression, but was able to recover and was again issuing dividends by 1935.

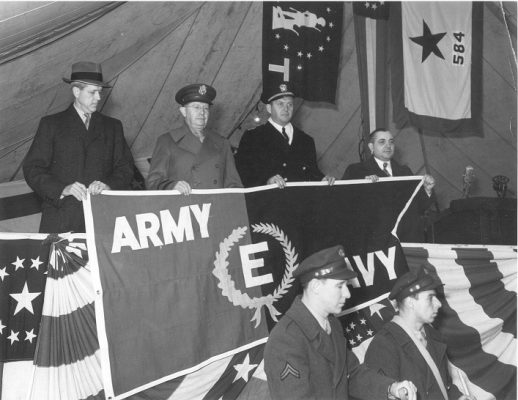

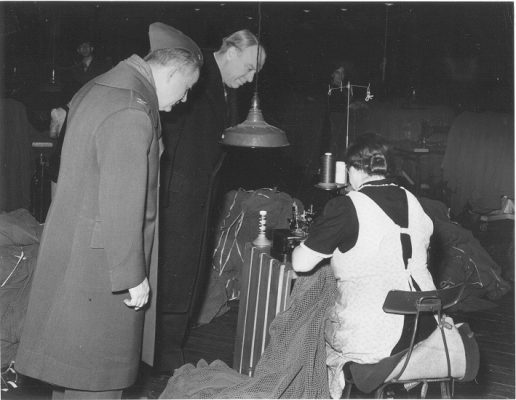

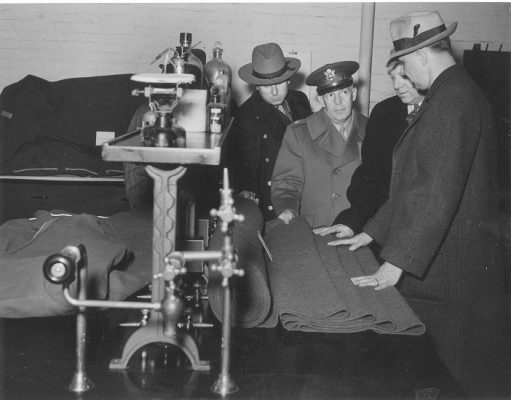

During World War II production at the plant turned to materials and equipment for the war effort, including $56 million in blankets, which was more than any other manufacturer. Also produced were enormous quantities of duck (a canvas) and rubber coated nylon and rayon for tires. The mill’s machine shops produced parts for submarines, planes, radar, and even secret/classified projects.

The post-war boom brought total employment to 9,000 in 1948. Increased prices resulting from wool shortages during the Korean War, along with labor troubles, however, resulted in major losses in 1951. At this time mergers with southern companies resulted in the creation of a new Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Co., Inc. – now a Delaware-based corporation. In 1958 the Thompsonville plant was sold for $1,300,000 to Kratter Associates, who then leased space back to the failing carpet operation. Production was gradually shifted to more modern, less expensive to operate southern factories.

By the 1960s, attempts were being made to use the buildings from Enfield’s rapidly declining carpet industry for other manufacturing purposes. Some small businesses rented space in vacant mill buildings. One example was the National Metal Specialties Company, which manufactured products including steel Christmas Tree stands. It only employed a handful of people

Perhaps the most ambitious attempt was made by the Bigelow-Sanford Carpet Corporation itself. In 1960, Bigelow-Sanford purchased a majority stock interest in Crestliner, Inc., a manufacturer of fiberglass and aluminum boats ranging in size from 12 to 19 feet and selling for prices between $215 and $2,300 (1960 dollars) for $2,250,000 as part of a diversification strategy. Crestliner headquarters were to be moved to Thompsonville. Lowell Weicker (father of the future Connecticut Governor, U.S. Representative, and U.S. Senator of the same name) was named chairman of Crestliner’s board of directors, Bigelow-Sanford executive vice president William N. Freyer and comptroller Robert L. MacKenzie were appointed to the board, and Bigelow-Sanford vice president of finance, John A Donaldson, was appointed to the same position at Crestliner. Great excitement followed, with new boat models shown at regattas on the Connecticut River, and extensive coverage and publicity both locally and nationally. Unfortunately, timing is everything and the merger came at just about the worst time possible. Recreational boat sales plummeted at the time. Employment peaked at about 60 workers, far below predictions. All production workers were laid off in 1962 and all Thompsonville operations ceased in 1963. In one last bit of irony, Enfield’s Board of Selectmen adopted a new town seal on January 28, 1963 that features two boat propellers representing the local Crestliner boat plant, even as that plant was being shut down. Bigelow-Sanford sold Crestliner at a loss to Molded Fiber Glass Body Co. of Ashtabula, Ohio in 1964.

Despite years of attempts by local management to make the plant productive enough to be profitable, the mill closed in 1971 and was vacated by the next year. The empty buildings sat deteriorating for a decade before some of them were given a new purpose. The mill was redeveloped as apartments and office space during the 1980s. Several buildings were demolished to make room for parking and other amenities, while the remaining ones were completely refurbished. The renovated facility opened in 1988 with the buildings retaining much of the positive character of the original factory complex, but without the hum and rumble of industrial activity.

The Old Town Hall Virtual Museum