The Hazard Powder Company and the Hazardville Gunpowder Industry

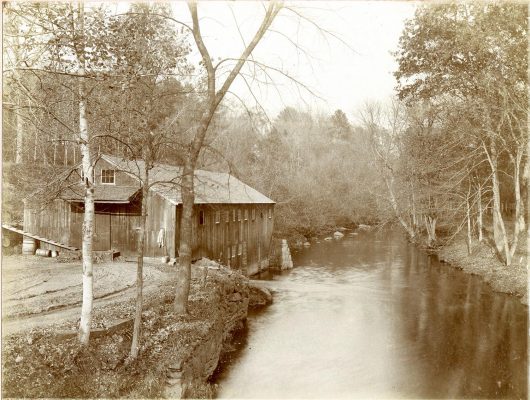

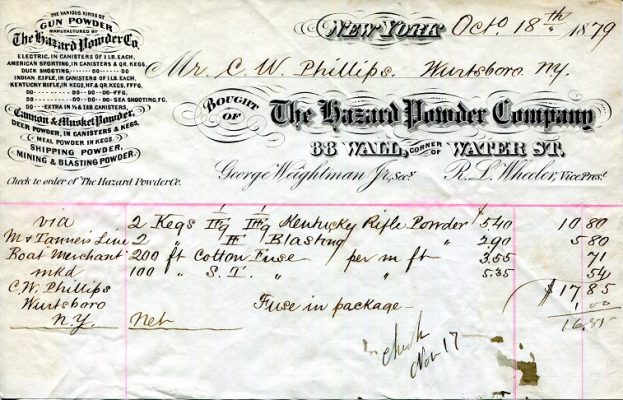

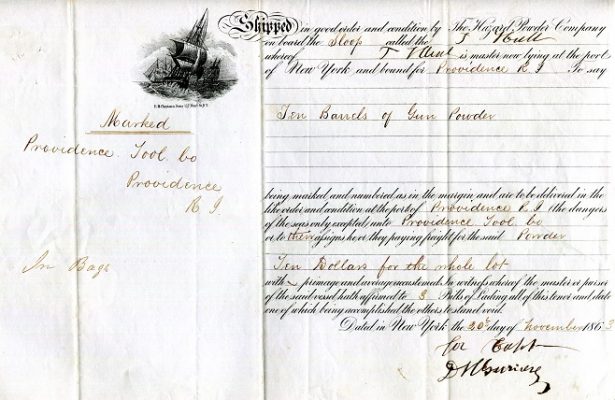

In 1835 the Loomis Brothers, Neeland, Parkes, and Allen partnered with New Haven businessman Allen Andrews Denslow to purchase 500 acres along the Scantic River in Powder Hollow from Sarah Allen, the widow of Doctor David Allen of Enfield, Connecticut. The following year the fledgling business incorporated in the state as Loomis, Denslow and Company. Skilled gunpowder workers were brought in from Faversham, England to assist in upgrading the powder quality and expand the small mill from a simple brass ball mill into a more conventional, large scale gunpowder manufactory. In 1837 Colonel Augustus George Hazard, previously engaged as the primary sales representative for the organization working out of lower Manhattan, NY, acquired a one quarter interest in the company.

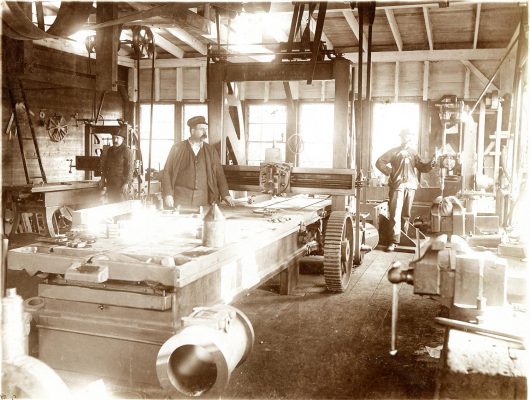

The manufacturing of gunpowder by mixing water, sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter in specific amounts was begun by grinding this mixture using heavy vertical wheels rolling through a circular bed trough. The mix had to be kept moist or the act of grinding might cause it to explode. The wet powder was formed into blocks in hydraulic presses. The resulting blocks were then cracked, or “corned”, with zinc rollers into a coarse powder which was then screened to obtain various size grains for different industries. Grain sizes could range from fine powder for small arms to softball size chunks for large cannons. The cracked powder was further dried and tumbled or “glazed”, then sifted once again and packed into canisters, kegs, and barrels.

The Loomis Brothers had made the bulk of their seed money in cigar manufacturing in Suffield, CT, in the early 1800’s, and had even partnered in the 1820’s with Augustus Hazard in owning small powder mills in and around Connecticut. Hazard was born in South Kingston, Rhode Island on April 28, 1802, but his family moved to a relative’s farm in Columbia, Connecticut when the boy was in his early teens. Unlike his relatives in Rhode Island, his line of the family was less successful, and Augustus was encouraged to go into the trades, specifically house painting. At the age of 20, moved to Savannah, Georgia, which had been devastated by fire, and opened a partnership with Allen Denslow dealing in paints and oils. There he joined the Georgia state militia where he picked up the title of Colonel, and a few short years later, along with his partner Denslow, won a parcel of 200 acres in the 1827 Land Lottery drawing

The business was very successful, and he mirrored his southern success by opening a sister store in Manhattan. Later Hazard sold this New York business to an employee, Tillinghast Tompkins, and set up shop as a merchandising agent and part owner of packet ships between New York and Savannah.

The business panic of 1837 caused Colonel Hazard huge losses, but he was able to fully recover, pay off all debts, and emerge stronger than before the panic. On March 23, 1843, Parkes, Allen, and Neeland Loomis, Augustus G. Hazard, and Allen A. Denslow quietly dissolved Loomises, Hazard & Company. The company was purchased by a group of investors with Colonel Hazard as the principal new owner. Hazard moved to Enfield, built a very fine mansion (since destroyed by fire) and was visited by many important persons during his years in the town, including Daniel Webster, Samuel Colt, and Jefferson Davis.

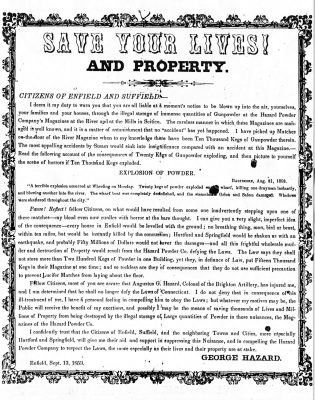

The gunpowder business was – excuse the pun – booming. The war with Mexico in 1846, the 1849 California gold rush, and the 1854 Crimean War all brought huge orders for gunpowder of all types. In 1849 Paul Greeley, Tudor and Frank Gowdy, and Wells Loomis formed a competing company – the Enfield Powder Company.

On the same evening as the barns of John King, principal owner of the Enfield Powder Company burned to the ground, Albert Olmstead, Esq. of Enfield, a member of the State House of Representatives was called to Chair a meeting of the residents of the west end of Enfield where a motion was made and passed name the carved-out village Hazardville in honor of the Colonel himself. Four years and multiple casualties later, Enfield Powder was absorbed by Hazard Powder.

The Hazard Powder Company survived the depression of 1857 because of strong demand for powder for railroad construction and metal mining in the west, as well as cooperation with du Pont.

Colonel Hazard’s personal fortunes were not so good. Both his sons died – one of consumption and one, tragically, in an explosion while proving gunpowder.

Gunpowder is very dangerous to work with and numerous safety precautions were taken by the Hazard Powder Company to prevent explosions. Iron or steel tools were not allowed, as sparks could occur if they banged together or against a nail or spike. During the grinding phase of production, the gunpowder was kept moist to reduce the chances of friction throwing a spark. The men who kept the powder wet sat on one-legged stools, designed by Alfred Nobel of the Nobel Prize fame, so that they would fall over and wake themselves up if they dozed off – a few bruises were better than blowing up. Employees were not allowed to bring pipes or matches into the hollow, and horses were shod with copper shoes.

Despite these precautions and others, explosions were expected so large stone blast walls were erected to separate buildings to prevent explosions from destroying multiple buildings. Each operation in the process was addressed and shared among multiple buildings as redundancy would allow for production to continue should a calamity befall the site. The buildings themselves were designed to blow apart and to be easily put back together – walls would fall outward relatively intact and the frames were huge so that any fire could be put out before enough damage occurred to them. Even though explosions did occur over the years, the Hazardville operation was unusually safe with only 67 deaths during nearly eight decades of operation.

The gunpowder business in Hazardville was a million-dollar business by the outbreak of the Civil War with wartime capacity reaching 12,500 pounds per day. At this time the plants were described as follows: This Company has eighteen sets of rolling mills with thirty-six iron wheels, each wheel weighing eight tons; seven granulating mills; five screw press buildings; and three hydraulic presses of 500 tons each, in different and separate buildings; and about fifty buildings used for dusting, assorting, drying, mixing, pulverizing, glazing, and packing houses-with extensive saltpeter refineries and magazines, cooperage, iron, woodworking, and machine shops- in all, about 125 buildings at their main works at Hazardville and Scitico, extending over a mile and a half in length and half a mile in width. To propel this vast amount of machinery, twenty-five water wheels and three steam engines are required.

The end of the Civil War brought hard times as the government auctioned off huge amounts of surplus powder. Competition became brutal as the powder companies fought for survival.

On May 7, 1868, Augustus George Hazard, owner of the largest gunpowder company in the country, mercifully died at the Fifth Avenue Hotel after a long bout of smallpox and pleuro-pneumonia. With no clear successor the company was directionless and began to flounder. Three years later in 1871 a huge explosion destroyed much of the plant, and two years after that the entire country felt the effects of yet another business panic. In 1876 the stockholders sold out to du Pont, although the sale was not publicly announced for another decade.

In 1872, just prior to du Pont’s purchase of the Hazard Powder Company, DuPont, the Hazard Powder Company, and Laflin and Rand formed the “Gunpowder Trade Association of the United States” to restore a sense of pricing normalcy to the industry. Health was restored by purchasing and closing smaller companies, discouraging new companies from starting, and fixing prices. On July 2, 1890, President Harrison signed the anti-monopoly Sherman Act, but it was some years before this had any impact on the gunpowder industry. Finally, on July 31st of 1907, the Department of Justice brought suit against the DuPont organization claiming a monopolization of the industry, with a former Hazard sales agent providing damning testimony.

As a result the explosives business was divided into three firms: Hercules Powder, Atlas Powder, and E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. The Hazard mills were transferred to Hercules on December 15, 1912, with the site formally renamed. Less than a month later, on January 14, 1913, a huge explosion heavily damaged the plant and killed two workers. The damage was so extensive that the mill was permanently closed, the equipment moved to an alternate site at Valley Falls, New York.

Today little remains of the Hazardville gunpowder industry with only one or two buildings, street names like “Cooper Street,” empty canals, and a few old stone foundations and blast walls honoring the former facility. Many old canisters, kegs, barrels, and other artifacts survive in private collections with some of these, along with photos and the story of the Hazardville gunpowder industry, preserved by the Enfield Historical Society at the Old Town Hall Museum.

The Old Town Hall Virtual Museum