For thousands of years people have made things in Enfield. The earliest evidence of this is the hundreds of Native American arrowheads, spear points, drills, hammers, axes, and more that have been found here over the years. The European settlers who came to live in Enfield in 1680 and their descendants were by necessity farmers, but they also had to make things needed for daily life. It would be many years before they could go to the store to buy the necessities. Even before Europeans lived in Enfield, Springfield’s John Pynchon built a sawmill on Freshwater Brook and began making lumber from the area’s abundant trees.

Immigrant blacksmiths, carpenters, furniture makers, silversmiths, and other artisans practiced trades they learned in Europe, usually bartering their products with other settlers for food, labor, and other made goods. These men passed their skills down to sons and apprentices – but not daughters, which would come much later. Which is not to say that women were not making things here. Their labors produced many things needed for survival. Women were spinning wool and flax into yarns and threads, weaving cloth from those yarns and threads, and sewing clothes from that cloth. They were making soap and candles and many other things needed in the home. The importance of these products should not be underestimated as many were needed simply to survive.

Enfield’s size meant that there was a lot of room for farms. But farming was very labor intensive and for decades Enfield’s citizens subsisted on the products of their own farms, with no capacity for commercial agriculture. This changed with improved technology in the 1800s and agriculture became an important part of the town’s economy, enough so that farming is the subject of its own exhibit.

Perhaps Enfield’s most transformative natural resource was its rivers and streams. The Connecticut River became an important transportation highway, despite the obstacle presented by the Enfield Falls, or Enfield Rapids as we know them today. The Connecticut River provided a way for Enfield’s products to be shipped up and down the East Coast and beyond. Perhaps surprisingly, the much smaller Scantic River and Freshwater Brook – or Asnuntuck Brook as it is also known – were key to Enfield’s industrial past. They provided power for Enfield’s first industries.

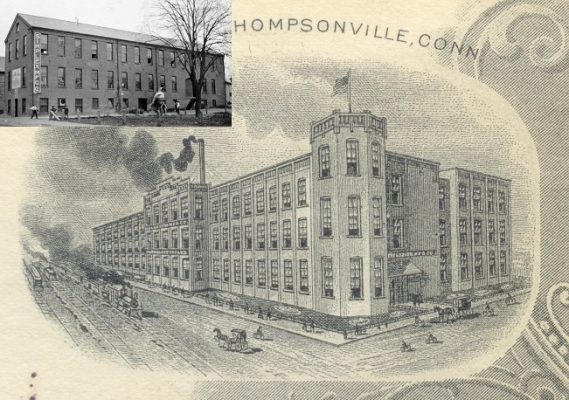

Enfield’s first industrial center was on Freshwater Brook in the area that became Thompsonville. John Pynchon’s 1660s sawmill was the first mill on the brook, but far from the most important one. Arguably, that was the 1829 White Mill, Orrin Thompson’s first carpet mill and the beginning of a huge industry with an international market that lasted for over a century and gave Thompsonville its name. The carpet mills are the subject of their own exhibit.

At the same time and farther east in the Scitico section of Enfield dams were built on the Scantic River to power mills from an array of smaller industries. One greatly expanded and became Enfield’s second industry with an international market and a founder who had part of Enfield named after him – Colonel Augustus Hazard’s Hazard Powder Company. The gunpowder industry is the subject of its own exhibit.

Enfield’s industries needed more than power to succeed. Transportation of raw materials into Enfield and finished products out of Enfield were also critical. Flatboats with their shallow draft were the earliest practical option for transportation through the shallow stretches of the Connecticut River in and below Enfield. But they were limited in capacity, slow since they were powered by teams of men poling the boats, and unusable when the water was too low, too high, or frozen. When steamboats came into use, they could occasionally travel through Enfield but usually only during the spring freshet when the water was deep enough. Fortunately, two important transportation infrastructure improvements came at just the right time. First, in 1827 construction was begun on the Enfield Falls Canal, now known as the Windsor Locks Canal. With its opening steamboats could bypass the falls (rapids) and reach Thompsonville and beyond, at least when the river wasn’t frozen. Even more importantly, in 1845 the railroad reached Thompsonville. A second line reached Scitico in 1876. It became easy and relatively inexpensive to send Enfield products almost anywhere in the United States and beyond.

Another critical resource was skilled labor. At first, skilled workers were brought in from Europe: weavers from Scotland for the carpet mills and experienced gunpowder makers from England. As the number of factories increased, so did the number of skilled laborers, either attracted to the area by the available work or trained here. Unskilled workers were needed as well. Thompsonville’s population grew greatly, driven mostly by the rapidly expanding carpet industry and the thousands it eventually employed, their families, and the many people working in the stores and other businesses that every village needed. All these people provided a ready pool of labor that attracted more businesses and small industries to Thompsonville. In contrast, the industries in Scitico and Hazardville needed a much smaller labor force, and those parts of Enfield grew much more slowly.

Raw materials were also needed. These were found locally at first. Lumber for the sawmills, bog iron for early iron production, grains for the distilleries. But Enfield’s rapidly expanding factories soon required much more raw material than could be supplied locally. Fortunately, water and rail transportation made it possible to bring these materials from wherever they could be found, whether it was wool or saltpeter from the other side of the world, iron and coal from the Midwest, or any of a myriad of other raw materials.

One last resource was needed. Money. Cash was needed to build and expand mills and fill them with the needed machinery, hire the workers, purchase raw materials, and market and ship the finished products. Some of this money came from local investors but much came from outside of Enfield. Investors from Hartford, New York, Boston, Georgia, and more poured cash into the carpet and gunpowder industries, as well as some of Enfield’s smaller factories.

With all of these resources available and a location in the heavily industrialized Connecticut River valley, it was inevitable that inventors and investors would start many manufacturing businesses in Enfield. Their factories achieved varying degrees of success.

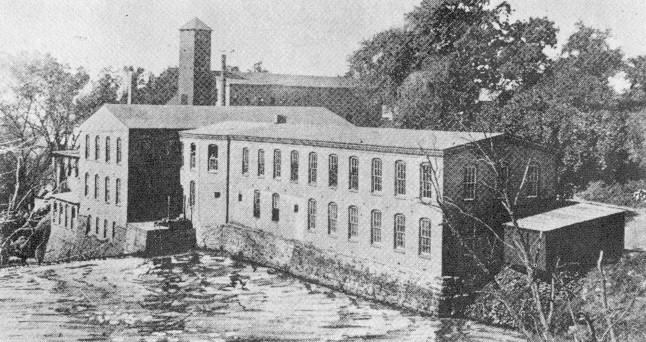

In 1845, the Enfield Manufacturing Company was incorporated, with Orrin Thompson’s son H. G. Thompson as president. Located south of the carpet mills on Asnuntuck Street, the company manufactured stockinet, a machine-knitted elastic fabric, and hosiery and underwear made from stockinet at the time when homemade clothing was being replaced with factory-made, standard-sized clothing. Women throughout Enfield were hired to assemble undershirts and similar clothing, sewing them at home and paid by the piece. The company also built a mill on the Scantic River in Scitico. The Enfield Manufacturing Company was in business for about three decades before folding by 1880. The Thompsonville building was taken over by the Hartford Carpet Company. The Scitico factory was sold to J.D. Stowe who used it to manufacture manila paper. Unfortunately, the Thompsonville factory burned to the ground in 1887 and the Scitico factory burned down in 1905.

In 1895, the H. A. Lozier Bicycle Company of Toledo, Ohio, one of approximately 700 bicycle manufacturers at the time, built a factory for manufacturing components for their bicycles on the still-vacant site of the former stockinet mill on Asnuntuck Street. In 1896, Lozier offered to move their main plant from Toledo, Ohio to Thompsonville if the Thompsonville Board of Trade gave them free land and “a $100,000 loan at 4 per cent.” The board of trade refused, whether out of inability to do so or unwillingness to take the risk is unknown. Either way, it was a good choice. In 1900, the H. A. Lozier Bicycle Company was swept up in a series of buyouts and mergers and became part of the American Bicycle Company. All machinery and materials from the Thompsonville factory were packed up and shipped to another factory in Westfield, Massachusetts.

The Pope Manufacturing Company of Hartford purchased the vacant Lozier factory in 1903, then leased it to the United States Graphotype Company, a manufacturer of typesetting machines. Little is known about the United States Graphotype Company’s activities in Thompsonville, but they too were quickly out of the picture leaving the building vacant again.

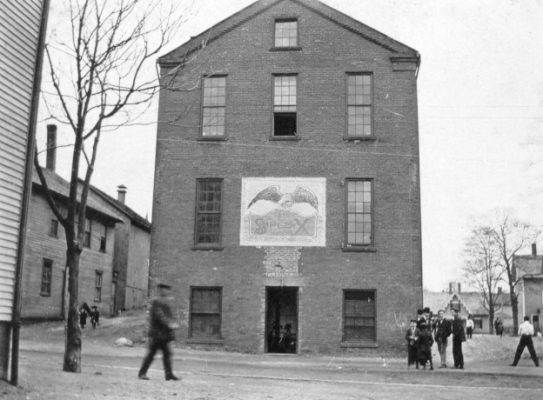

The next confirmed use of the former Lozier factory is by the Simplex Manufacturing Company, which moved from Granby, Connecticut to Thompsonville in 1908, lured by an $800 offer from the Thompsonville Board of Trade to help finance the move. By the next year employees were reported to be working overtime producing machines for affixing stamps and labels to envelopes, as well as coin separating machines. Only four years later in 1912 Simplex went into receivership and the factory closed, leaving about 30 employees without work. The Simplex stockholders, many local, lost all of their capital investments.

Later that year the building was sold to the Extensive Manufacturing Company of New York, manufacturers of machine tools, for $5,000. Extensive was more successful and outgrew the space by 1916. Unfortunately, they could not find an adequate facility in Enfield, closed the plant, and left town.

Other businesses, including the Hartford Carpet Company, used the building over the years. It was home to the VFW when it was torn down in 1998.

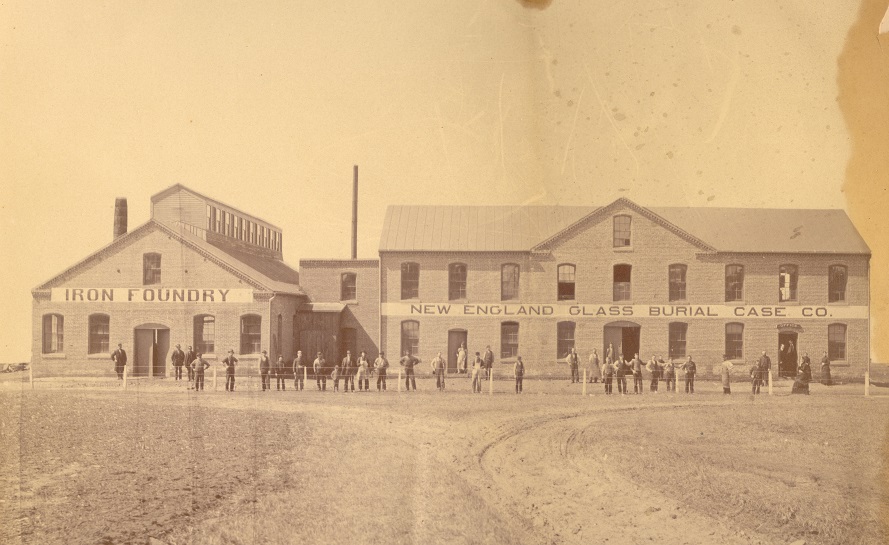

In the 1880s Prospect Street was an up-and-coming industrial area. Located conveniently near to the railroad line, it was an ideal location for factories and other commercial enterprises. One of the first got its start in May of 1881 when Joseph Askins of Elida, Ohio arrived looking for investors in a factory to build glass burial cases based on his patents. He already had two other factories, one in Ohio and the other in Ontario, Canada. Within a month he had enough investors, mostly from Enfield, and the New England Glass Burial Case Company was formed. Ground was broken in July and most of the factory was up and running by December. The first casket was completed and sold in January of 1882, only eight months after Askins made his pitch to investors. An addition to the factory for building wooden caskets was completed in October, seemingly a sign of expansion for a booming business, but actually an attempt to get into a market for a product that was in demand, which the glass burial cases were not. The company started making “full metallic caskets” in 1883, another sign that the glass burial case business was not succeeding. In January of 1884 most of the employees were let go and in March the board of directors shut down the factory. By 1885 the business was dead and the stock worthless.

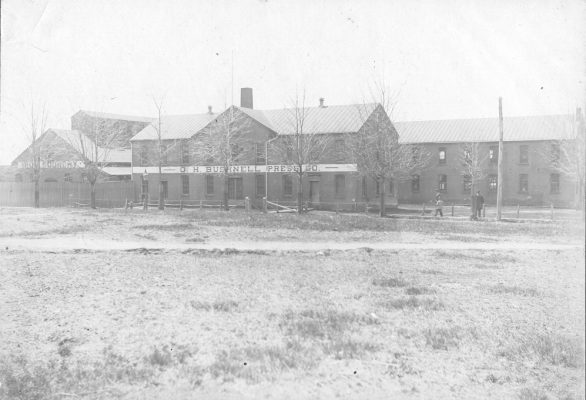

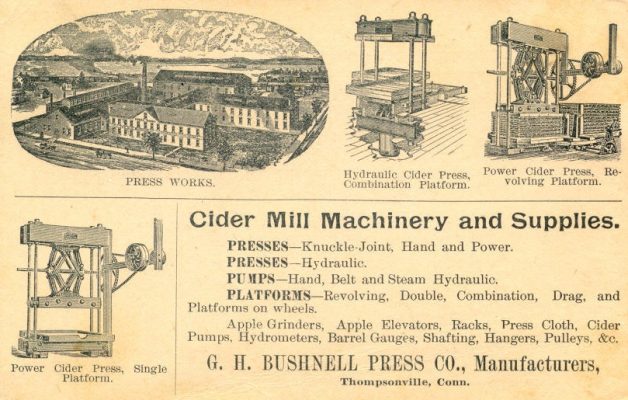

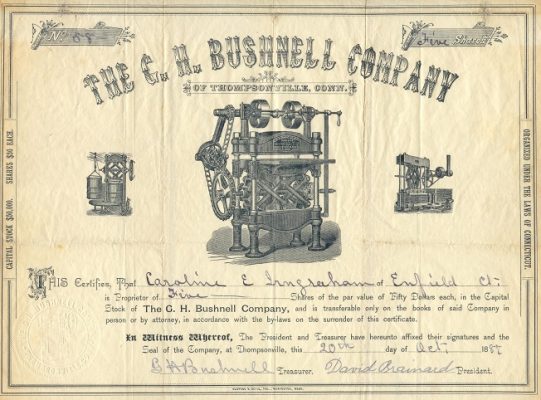

The New England Glass Burial Case Company’s buildings stood vacant for a couple of years, except for the foundry, which was operated for a while by one of the former employees, making castings for other local factories. This changed in 1887 when the G. H. Bushnell Press Company relocated from Worcester, Massachusetts to the Prospect Street factory. Bushnell manufactured industrial presses and other heavy machinery. While the presses were products of the company’s own design, Bushnell also made looms for the carpet mills and other machinery made to other companies’ specs for those companies’ use. Bushnell’s most unusual product may have been sewage presses used at the 1893 Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) to press water out of sewage to allow it to be more easily transported away and disposed of. The company went into receivership in 1893. A local man, James A. Colvin purchased controlling interest in the company in 1894 and returned it to profitability. In 1916, another of Colvin’s companies, the Standard Metal Works, which made exhaust pipes and other parts for automobiles, purchased Bushnell. In 1922 the combined business was sold and manufacturing was relocated out of Enfield. All of the buildings remain today and have been occupied by a lumber yard and home improvement store for many decades.

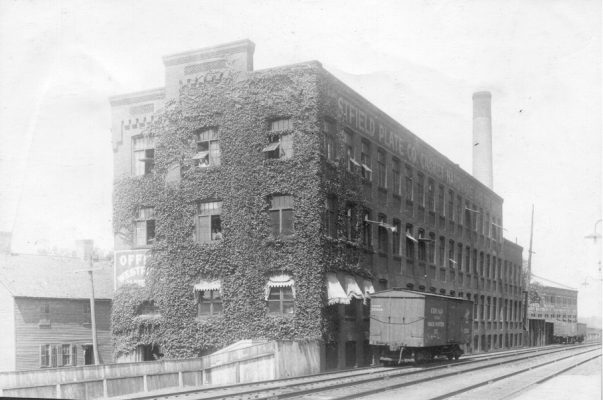

At the very same time that the New England Glass Burial Case Company was collapsing, the Westfield Plate company was being formed. Westfield Plate made parts for caskets, not complete caskets. The factory was up and running by August 1885. It was destined to be far more successful than the New England Glass Burial Case Company. Westfield Plate merged with International Casket Hardware in 1919 and continued to operate for several more decades. The building was taken over by Dow Mechanical in 1954.

Walter Dow of Thompsonville was an inventor and manufacturer. He received patents for several devices, including for a portable honing device, an internal length comparator gauge, and a cartridge head space gauge for rifles. Dow also received patents for car accessories, including disposable window sunshades, a bracket for positioning car visors, and a series of patents for “accelerator controlling devices.” He successfully operated his manufacturing business for several decades.

In Scitico, the Gordon Brothers built a large brick factory on the Scantic River in 1901 to manufacture a product with a name that seems destined to be a marketing disaster to today’s ears – shoddy. But shoddy was simply the name for recycled wool fiber and the mill was quite successful, often buying waste wool from other mills, processing it, and selling the resulting material back to the original mills. Relics from processing shoddy still occasionally turn up downriver – buttons from recycled clothing and ceramic stoppers from acid jugs. About 1940 part of the mill was acquired by the A.W. Dodge Company, which continued to produce shoddy. In 1948 the unoccupied part of the mill was acquired by DeBell and Richardson, which specialized in plastics research and development. In 1952, DeBell and Richardson purchased the entire complex, and later expanded the plant in 1964. In 1972, a second expansion was completed when the company was purchased by then-president Robert C. Springborn, who also changed the company name to Springborn Laboratories. Services were expanded to include testing, analysis, and quality assurance (perhaps ironic for a building built for “shoddy” work) for several industries. A series of sales, mergers, and splits led to name changes to Springborn Testing and Research and later to Specialized Technology Resource, Inc., or STR in both cases. While the buildings still stand today, they are now home to a brewery and winery.

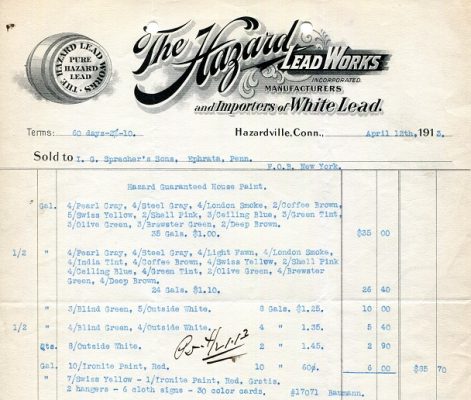

Incorporated in 1904 by H. Stephen Bridge, Charles C. Mann, F. A. Pickering, and William H. Whitney, Jr., The Hazard Lead Works’ first factory was a rented building on the Amos D. Bridge property in Hazardville. The factory housed three mills for grinding white lead (a toxic lead compound) and a steam engine to power them. The Hazard Lead Works initially made white lead paint and oil-based colors for tinting the white paint. The business was so successful that a second factory was opened in Brooklyn, New York in 1907. Sales reportedly doubled every year. To remain competitive, they eventually produced a full line of paints and varnishes, including pre-mixed colored paints. An article in the Thompsonville Press 1911 Industrial Edition claimed that Hazard paint was sold in 90% of Connecticut’s towns and “almost every city and village in the United States,” undoubtedly an exaggeration. Further, “the goods are distributed from Maine to Florida and from the Atlantic coast through all sections of the middle west and southwest.” This was perhaps a more accurate picture of their market, given that they had offices in New York, Boston, Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, and, of course, Hazardville at the time. All production and operations moved to the Brooklyn factory sometime after its completion and the company does not appear to have lasted past the 1930s. The Hazard Lead Works was not connected with the Hazard Powder Company, although both company’s names were rather appropriate, one producing explosives and the other lead-based paints, known even at that time to be dangerous.

Not all of Enfield’s manufacturers were selling to national or international markets. Many were selling strictly locally to Enfield and surrounding towns. Some produced very small numbers of items, others were fairly large in scale. Henry Alden’s brickyard on the north side of Alden Avenue at the intersection with Springfield Road and Maple Street (both now part of Enfield Street) was at the large end of the scale. An item in the May 14, 1885, Thompsonville Press gives an idea of the scale of manufacturing: “The bricks for the Westfield Plate Company’s new building are being furnished by H. D. Alden. Mr. Alden has also contracted to build a brick school house at Windsor Locks which will use about a hundred thousand bricks.” His brickyard made bricks from clay dug in Enfield. Production had reached 40,000 bricks per day when he sold out to Lewis K. Brower and John A. Best in 1906. Bricks made by them have a raised B & B on their tops and are found in structures all over the region.

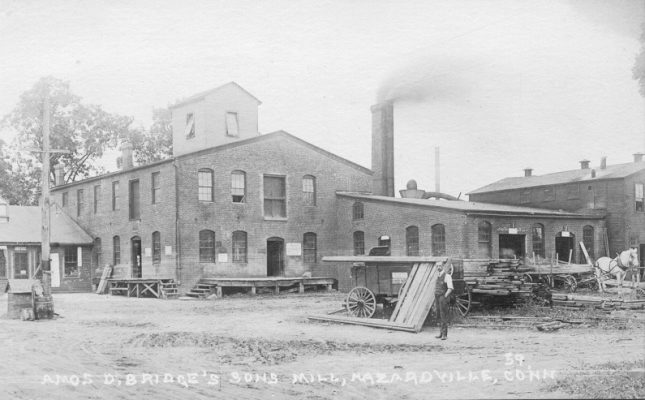

Lumber mills owned by Amos Bridge and his sons in Hazardville and Theodore Pease and his sons in Thompsonville produced lumber from locally and regionally sourced trees into the early twentieth century. Many Enfield homes, barns, and businesses – and some of their wooden furnishings – were made from lumber sawn in those mills.

Cabinet and furniture makers were in some ways the handymen of their day. Not only did they use their skills to build cabinetry and other finish carpentry work in homes, and to build custom furniture, but they also performed repairs on most household furnishings made of wood. Many supplemented their income by building coffins (everyone needed one eventually) and often also provided full undertaking services. John Loring was originally from Maine. He moved to Thompsonville after serving in the Civil War. Loring was a cabinetmaker by trade, but, like many cabinetmakers of the time, he supplemented his income making wooden coffins and providing undertaking services. Two things set John Loring apart from the other cabinetmakers in town. First, he served as the local Justice, presiding over many cases. Second, he made very fine violins and at least one cello, some of which are still played today.

Joseph Bent and Charles Miller were two Thompsonville manufacturers of carriages, wagons, and sleighs. Enfield blacksmiths shod the horses that pulled those vehicles and the countless plows used on Enfield farms. Some of those plows were made in Enfield by Albert King and others. Many more plows were shipped south, at least until the Civil War closed that market.

These are just some of the stories of Enfield’s manufacturers and industries, large and small. Many other stories are waiting to be pieced together from documents and photos in the Enfield Historical Society archives and in places where boxes of dusty old documents and artifacts are waiting to be found. Some stories are unfolding today, and some are yet to begin. Things are still made in Enfield – aerospace parts, medical devices and supplies, industrial valves, and more. But for now, the scale of manufacturing is only a fraction of what it was during Enfield’s manufacturing heyday of the 1800s through the mid-1900s.

The Old Town Hall Virtual Museum