Enfield’s first settlers were farmers by necessity. Their survival depended on the crops and livestock that they raised. Each adult male settler was granted a 10- to 14-acre plot of land for their home and farm. These plots extended from the main road (today’s Enfield Street) either west to the Connecticut River or east a similar distance. Each settler was also given between 30 and 60 acres of meadowland to be used for grazing livestock, primarily cattle, sheep, and some horses. Other livestock, like pigs, chickens, and geese, were kept nearer to home.

Just living was hard work, as each settler had not only to clear their own land, maintain their property and fences, and raise their own crops and livestock, but also spend a required number of days each year maintaining the town’s roads and communal property. Many of the towns’ earliest laws spelled out these duties. Other laws specified the penalties for damage caused by roaming livestock. In a time where starvation was only one bad crop away, having your escaped cattle eat or trample a neighbor’s crops could be devastating.

Subsistence farming remained the main activity of the majority of Enfield citizens for most of the 1700s, although a few practiced trades like blacksmithing and cabinet making. Payment for products and services in those early days was often in crops or livestock, or in materials like firewood or boards, or even in physical labor. This was also often true for taxes.

Despite the challenges of eking out a living, the population grew steadily and farms sprang up across Enfield.

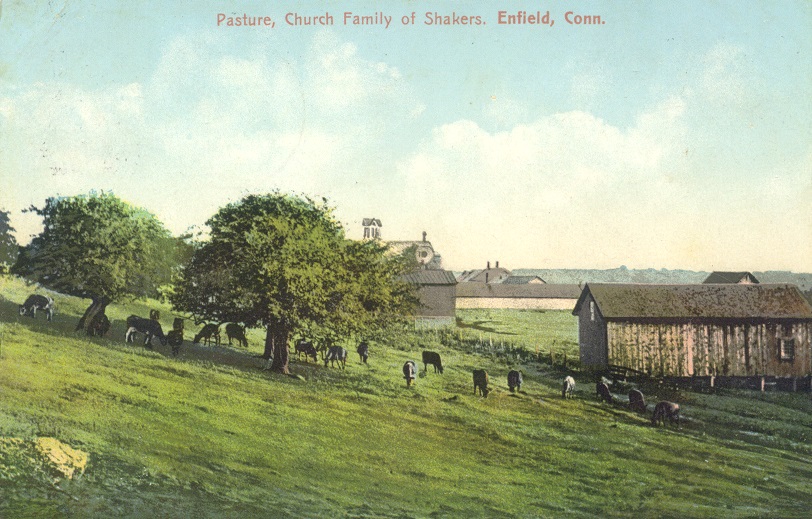

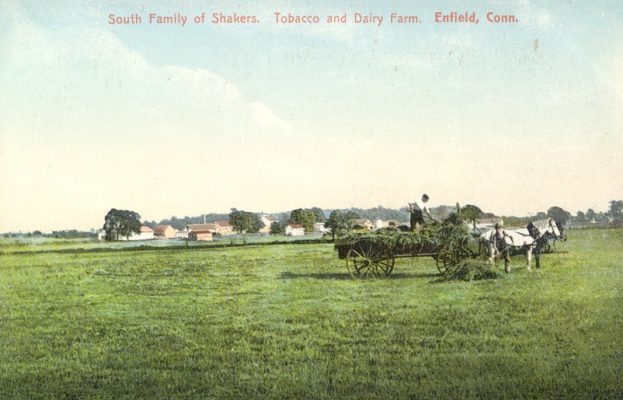

Conditions began to improve for farmers after the Revolutionary War. By about 1800 improvements in farming methods meant that crops and livestock could be raised for sale to people living in bigger towns and cities and even for export to Europe and other parts of the world. At the same time, gin distilleries were becoming quite profitable and many were built in area towns including Enfield. This created a commercial demand for rye, another local crop. The byproducts of distilling gin proved to be good feed for beef cattle, which were raised locally and sold in cities like Springfield and Hartford. The Enfield Shakers began producing pre-packaged vegetable, flower, and crop seeds, which they raised on their land and also purchased from other local farmers. In fact, the Shakers invented the concept of selling seeds in packets, as seed had previously been sold in bulk containers and measured out for customers by retailers. Packets of Shaker seeds were sold all over the United States. Whichever crop or livestock they were selling, farmers began to earn real money and to spend that money on manufactured goods, which in turn allowed more people to earn their living as artisans, merchants and factory workers-a new option for making a living. Still, most of Enfield was farmland.

The post-Civil War years were hard on local farmers. Federal taxes on gin closed down distilleries and hit the rye farmers hard. Beef farmers were forced to change to less-demanding dairy cattle for lack of the “still swill” used to quickly fatten their cattle. The war had effectively closed the southern market to the Shakers and devastated their seed and herb businesses. Western farms were producing crops on a scale previously unheard of and at prices that were hard to compete with. The result was many lean years for local farmers.

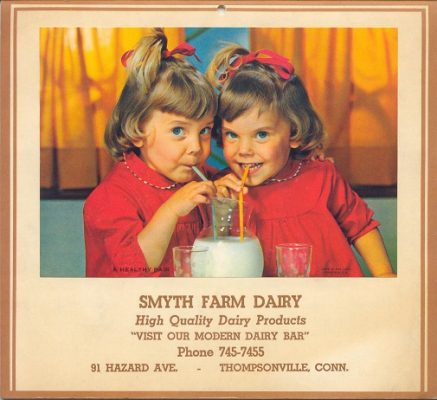

Fortunately, some farm products were always needed, dairy products among them. Prior to the availability of mechanical milkers, dairy farmers were limited to about 10-15 cows, which was all that they could milk by hand. So, there were a lot of dairy farmers, each producing small volumes of milk that were sold raw to local families or sent off in milk cans to commercial bottlers. With the invention of milking machines, the number of dairy farms dropped while at the same time the sizes of dairy herds increased. Some farmers began to bottle and deliver their own milk, while others pooled their products in co-ops. Evidence of these changes is seen in the milk bottles to be found from Enfield dairies with names like Allen Brothers, H.S. Reid, Polish Co-op, and many, many more. Today, only a couple of dairy farms remain in Enfield, and only one bottles their own milk on site.

Vegetable-only farms did not exist for most of Enfield’s first two centuries or so. It was not that vegetables were not grown, it was that they were grown on farms that raised a mix of crops and livestock. Most vegetables were grown for consumption on the farm and generally only less-perishable root crops were grown for market. It was toward the end of the nineteenth century that farmers found that raising vegetables for sale in neighboring cities was profitable enough to justify specializing in vegetables. Today there is a seasonal demand for locally-grown vegetables and a few small or very small farms raising and selling them.

As the twentieth century arrived, so did a new cash crop. Well, not exactly a new crop. Tobacco had been grown since Colonial times, but it was a poorer quality native variety that required a lot of labor to plant and grow. By 1900, new varieties of tobacco were imported from the West Indies that were much better than the local variety. At the same time, horse-drawn machines called tobacco setters had been invented that greatly speeded the planting process. By 1910, Cuban tobacco varieties had also been imported. Cuban tobacco required tropical conditions to grow and it was discovered that growing it under tents of loosely woven cloth would create these conditions. Although known as shade tobacco, a name that brings thoughts of relaxing under a shady tree on a hot day, the reality is that the tents increased the heat and humidity for the tropical tobacco plants enough to allow them to grow quite vigorously. With these improvements, tobacco became a highly profitable crop. Enfield farmers had the perfect land to cash in and by the early 1920s about 1500 acres were planted on 200 farms. Tobacco farming peaked by the mid-century when it seemed that every teenager in town worked on the farms during the summer. There are still some tobacco farms today, but only a fraction of the acreage compared to the peak years.

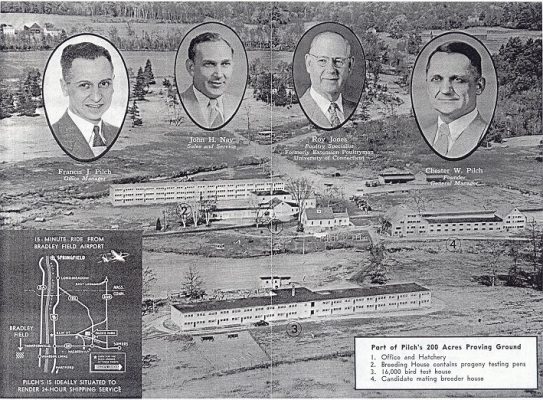

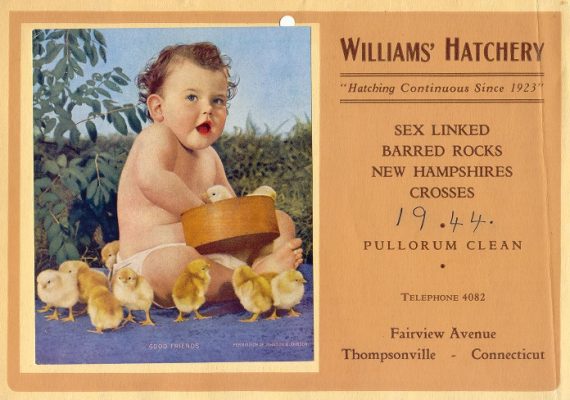

The poultry business also boomed during the twentieth century. Some Enfield farmers raised chickens for the table, some to sell their eggs to hungry consumers, and others to sell fertile eggs or chicks to other farms. Farmers like George Poole, Lyman Norris, Ralph Moody, and others had thousands of chickens in their flocks. Chester and Francis Pilch had the biggest and most famous operation of all. At their height, they had 150,000 breeder hens producing 10,000,000 breeder female chicks annually; these chicks were sold to other commercial farms where they were used as breeders to hatch hundreds of millions of chickens for eating. The Pilch’s Enfield plant was also their international headquarters for nine subsidiary corporations and they had six plants in the United States, Canada, and overseas. The Enfield plant closed shortly after being sold to the Dekalb Corporation in 1969.

The 1960s started to see tobacco fields and dairy farms replaced by a new crop – housing subdivisions. A trend that would spell the end of most of Enfield’s farms over the next few decades.

The Old Town Hall Virtual Museum