The roots of Shakerism can be traced back to a small religious group who fled from persecution in France. In London, England they gained converts from the Quakers and Methodists. The new group, led by James and Jane Wardley, became known as the United Society of Believers. They believed in direct communication between man and God. Their religious meetings emphasized this communication. Members would sit in silent meditation until they received a sign or “vision” from God, at which point they would start to tremble, shout and sing. This behavior led their detractors to nickname them “shaking Quakers” or “Shakers” for short. The Society adopted this name officially and it soon became synonymous with quality and integrity.

One young Shaker woman, Ann Lee, would eventually lead the Shakers. Born to a large poor family in Manchester, England, Ann Lee lived a hard life. She was forced to earn her own living working in a factory and then as a cook. Still very young, she married a blacksmith named Abraham Stanley. They had four children, all of whom died in infancy. Despite these hardships Ann Lee remained strong in body and spirit. Deeply religious she often spent entire nights in prayer and had many visions. She became an aggressive member of the Society.

Because of her natural popularity and leadership qualities Ann gained a strong following. Her popularity unfortunately led her to be imprisoned several times by the English authorities. During her last imprisonment she envisioned the sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. From this vision came one of the basic tenets of the Shaker religion: no one living in the sin of “gratification of lust of the flesh” could be a follower of Christ.

Upon her release from prison Ann accepted the title of “Mother” and leadership of the Society. She began to preach that God was both male and female and that the second coming of Christ was in female form – through her.

Following another vision, Mother Ann and a few chosen followers sailed for North America on May 19, 1774. The group arrived in New York harbor and then split up to find work. Abraham Stanley did not share Ann Lee’s beliefs and they soon separated. The rest of the group made their way to Niskeyuna, New York where they devoted themselves to God and to spreading the gospel of Shakerism.

In 1780, Joseph Meacham, a New Lebanon, New York lay preacher originally from Enfield, Connecticut, was told about the Shakers and Ann Lee. He sent Calvin Harlow to verify what he had heard. Harlow returned convinced that Mother Ann was the second coming of Christ. Meacham then went to investigate first hand. After spending the entire day of May 10, 1780 questioning Mother Ann and her followers he too was convinced.

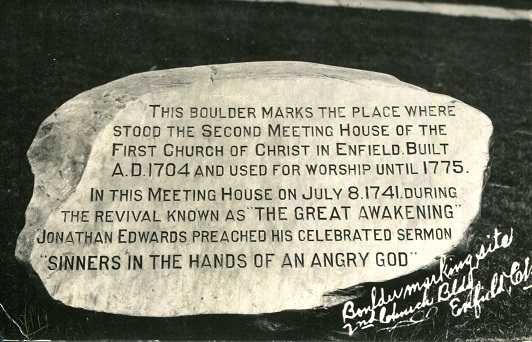

Ann Lee traveled throughout New England during the years 1781-1783. She first visited Enfield in 1781. Fearful townspeople broke up a religious service being held by the Shakers and threatened to tar and feather them. Fortunately, local Revolutionary War officer Elija Jones came to their rescue and escorted them safely out of town.

In 1782, Mother Ann’s second visit to Enfield didn’t go any better. She and her followers had been pursued by Captain Charles Kibbe and 20 to 30 men from Somers, who broke into the home of Joseph Meacham’s brother David where the group had taken shelter. John Booth, an Enfield constable, broke up the disturbance, but not before considerable damage was done to the house and David Meacham. The rioters were summoned to County Court in Hartford. They were offered the chance to settle without trial if they would confess their conduct before their own church. They refused and were put on trial, found guilty, and fined. That was the end of mobbing and rioting against the Shakers in Connecticut.

In 1783, Mother Ann’s third visit to Enfield was peaceful. It was also her last. She died at the age of 48 on September 8, 1784. Three years later Joseph Meacham, originally from Enfield, became the leading minister in the Society. Joseph Meacham realized that because of the difficulties of living a celibate life in a communal society it would be necessary to have a female leader with rights and authority equal to his own. He named Lucy Wright of Pittsfield, Massachusetts to this position. In 1792 the highest authority of the church, “The United Society of Believers, Shakers,” was established in New Lebanon, New York under the ministration of Joseph Meacham and Lucy Wright.

Though many converts had been made in Enfield starting with Mother Ann’s first visit in 1781, it was not until the same year that the New Lebanon community was established, 1792, that the Enfield, Connecticut community was formally established. Calvin Harlow and Sarah Harrison were sent from New Lebanon to bring the Enfield community into order, to guide and supervise the spiritual concerns of the community, to counsel, advise, and judge in all matters of importance, and to appoint elders, eldresses, deacons, deaconesses, and trustees for each “family.”

To become a Shaker a person had to:

- be free of all debts

- be free of all legal obligations

- make restitution by confession for all wrongs committed against any man or against God

- surrender all worldly goods to the Shaker community

- sign a covenant agreeing to the rules, regulations, and beliefs of the Society, including Christ’s second appearance in Mother Ann

The Enfield community grew to a total of five “families,” the North Family, South Family, East Family, West Family, and – at the center – Church Family. Their land encompassed somewhere between two and three thousand acres of land in Enfield and surrounding towns. The leadership of each family consisted of two elders and eldresses, two deacons and deaconesses, and two trustees. The elders and eldresses were appointed by the Church Family ministry, while the others were appointed by the elders and eldresses of each family. At its peak in 1855, the Enfield Shaker community had between 35 and 40 members per family. The elders/eldresses were responsible for the spiritual and physical well being of their family, while the deacons/deaconesses were responsible for the family’s domestic needs. The trustees were responsible for all business transactions with the outside world.

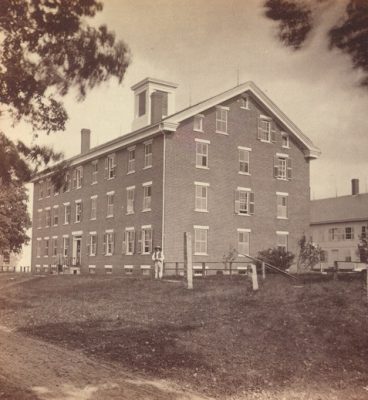

The Enfield Shaker community prospered during the first half of the 1800s. A thriving seed business founded in 1802 provided a sound financial foundation for the community. Sales of manufactured goods, ranging from bonnets to furniture crafted with the legendary Shaker quality and simplicity, also provided income. Many buildings were built, mostly of wood construction, although some, like the great dwelling house built in 1876, were of brick. The Shakers received numerous visitors, some of whom were converted to the Shaker religion. Being a celibate religion, conversion was the only way to add new members. Children of the poor, as well as orphans, were taken in and cared for by the Shakers, but were not required to join the community as adults.

Oddly for a group that lived separately from the “outside world,” for many years the Enfield Shaker community was a destination for travelers and diners. Meals were served to the public and visitors could vacation with the Shakers. Postcards and other souvenirs were sold to these visitors, who arrived from far and wide by train at Shaker Station or by horse and carriage (and later by automobile) from Enfield and nearby towns. Click here for an account of an 1865 visit to the Enfield Shakers.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the Shaker community began to decline. The religious, economic and social conditions that drove many people to join the Society in earlier times were changing rapidly. One by one the Enfield families merged as declining membership made them too small to operate independently. In 1913 the North Family was disbanded, leaving only the Church family. In 1917 the last eight Shakers in Enfield sold the remaining property to tobacco growers and moved to the Hancock, Massachusetts and New Lebanon, New York Shaker communities.

Today only a few buildings remain, including some South Family structures that are privately owned. The remainder of the surviving Shaker structures are on the grounds of Connecticut Department of Corrections facilities and are not accessible to the public.

Many artifacts and photos do remain. Most are in private collections. Some are preserved by the Enfield Historical Society and can be viewed at the Old Town Hall Museum and the Martha A. Parsons House Museum.

The Old Town Hall Virtual Museum